How to Turn Fear into a Compass | with Sam Potter

The Story

What happens when the thing that scares you most becomes the thing that shapes you? For Sam, the answer began long before the Emmys, in the small, wild corners of Kōloa.

Sam Potter grew up on the south side of Kaua‘i, where Saturdays meant Green Pond jumps, mango money, and cousins who felt like an entire world. The town of Kōloa shaped him early. Curious, restless, and never quite able to sit still.

“I didn’t fit into a lot of boxes… I wasn’t a very good student… I couldn’t sit still.”

That energy turned into a spark. A shoebox of dollar bills and mango profits became his first $400 camera. By high school, filmmaking returned to him like a calling. “Every day I prayed… give me something,” he said. And when his photography teacher told him to “film something,” he did — and felt something click.

But childhood wasn’t simple. Growing up haole in Hawai‘i meant bathroom fights, slurs, and confusion.

“I’m in second grade… I’m feeling hate.”

That pain hardened into a chip on his shoulder, a belief that belonging had to be earned through intensity. So he ran toward the things that scared him. He jumped higher cliffs. Took bigger risks. Tried to “out local the local boys.” He remembers standing on an 80-foot ledge surrounded by older kids, realizing this was the moment he proved he belonged and then leaping before fear could talk him out of it.

Moving toward fear became his pattern.

Filmmaking eventually shifted that. It moved him from proving himself to understanding himself. From seeking acceptance to sharing perspective. Years later, that journey would lead him to becoming a five-time regional Emmy Award–winning director, cinematographer, editor, producer, and host. All recognition earned through storytelling rooted in Hawai‘i, not driven by insecurity.

The turning point came when he realized he’d stopped giving aloha because he assumed he wouldn’t receive it. “I wasted so much time.” And that realization became the foundation for how he creates, leads, and grows.

The insight: Inferiority vs. Striving

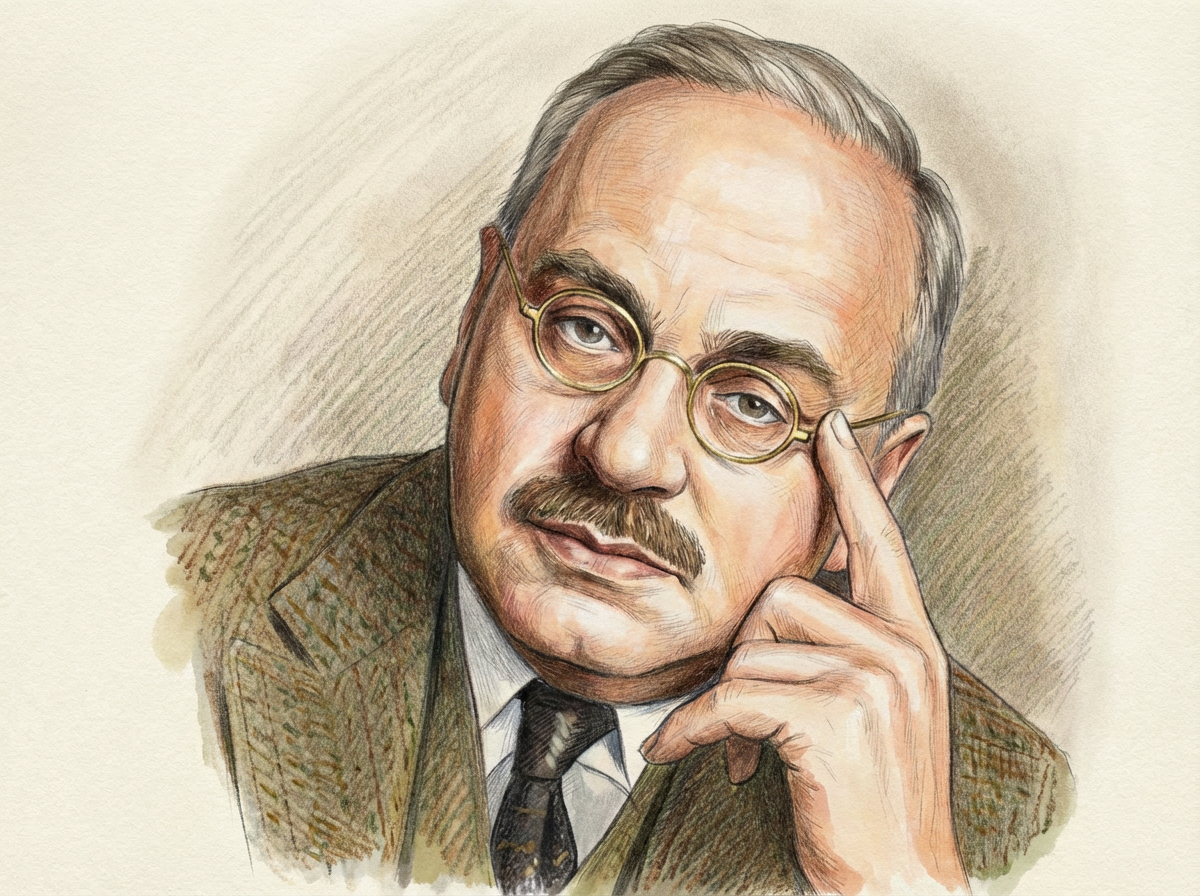

Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler believed something deeply human:

Everyone feels inferior at times.

Not because something is wrong with us, but because we are always growing into something we are not yet. From childhood on, we encounter limits:

not fitting in, not measuring up, not being accepted. Adler called this universal experience inferiority.

What matters, he said, is not the feeling itself, but what we do with it.

Adler described two paths.

When inferiority hardens into an inferiority complex, people withdraw. They protect themselves, avoid challenge, and interpret struggle as proof they don’t belong.

But when inferiority is met with courage, it becomes striving for superiority. Not superiority over others, but the drive to grow beyond who you were yesterday. This is striving as movement, effort, and becoming.

Sam’s childhood placed him squarely at that choice point. Growing up haole in Hawai‘i, being called names, feeling rejected — those experiences created real inferiority. But instead of retreating, he leaned in. He jumped the cliff. Took the risk. Tried to “out local the local boys.”

In Adler’s terms, Sam didn’t let inferiority become a verdict.

He treated it as information.

Discomfort wasn’t a signal to stop.

It was the engine that pushed him forward.

As Sam put it: “When I feel fear, I move towards it. It’s automatic.”

the application

Moments of discomfort are unavoidable. Feeling out of place. Not good enough yet. Behind where you want to be. According to Adler, these moments are not problems to solve; they are signals asking for a response.

And every time they appear, there is a choice.

One path is withdrawal. We shrink our effort, protect our image, and step back from challenge. Struggle becomes something to avoid, and inferiority hardens into limitation.

The other path is striving. We stay engaged. We accept being temporarily uncomfortable. We treat difficulty as part of learning rather than proof of failure.

Sam’s story shows how powerful that second path can be. Again and again, he chose movement over retreat. Not because the fear disappeared, but because he learned to treat it as information instead of judgment.

Growth doesn’t require confidence first.

It requires engagement.

When inferiority is met with striving, it stops being a verdict about who you are and becomes a direction for who you can become.

What We Can Steal

Treat inferiority as information, not identity.

Feeling behind or out of place doesn’t mean you don’t belong. It means you’ve reached the edge of your current ability, where learning and growth are possible.Choose striving over withdrawal.

When discomfort shows up, you always have a choice: step back to protect yourself, or stay engaged and let effort do its work. Growth only happens on the second path.Accept being temporarily uncomfortable.

Striving requires patience with yourself while your skills catch up to your effort. Discomfort is not failure, it’s the normal sensation of becoming capable.Move toward challenge before confidence arrives.

Confidence is not a prerequisite for action. It is built through repeated engagement with difficulty, one imperfect step at a time.

Mahalo for reading this week’s Mana‘o Bomb.

Next week, we’ll drop another idea from Hawai‘i. A story that sparks growth, resilience, and purpose.

Keep rising. Keep learning.