How to Find Your Path When Nothing Feels Clear | with Robynne Maiʻi

The Story

What if the path to where you belong doesn’t look like a path at all?

Robynne Maiʻi grew up in ʻAina Haina Valley, the middle child of three in a household where education was the family religion. Her mother was a high school teacher. Her father, an engineer. Both parents worked relentlessly so their children could attend the best schools in Honolulu. The expectation was clear: study hard, go to college, get a respectable career.

Robynne tried. She went to Punahou, then transferred to ʻIōlani. She was not a great test taker. She struggled in classes where the teaching was rigid. But if a teacher was engaging, creative, alive in the room, she locked in completely.

“It was just like if you were a good teacher, if you were fun, if you were exciting, if you knew how to teach well, I was totally on board.”

The signs were there early. Every favorite memory from childhood revolved around food. The “pusher” at Punahou lunch. Running through her dad’s kitchen. The third-grade Hawaiiana curriculum centered on kalo. But none of it pointed to a clear career.

“I just didn’t know. You just don’t know.”

So she searched. She considered law because she was stubborn and tenacious. She tried psychology in college and hated it. She declared a Japanese major to please her parents, then switched to modern dance and English because it actually excited her. She turned down a prestigious teaching job in New York to attend culinary school at Kapiʻolani Community College.

After KCC, Robynne moved to New York for a master’s in food studies at NYU. She landed a job at Gourmet Magazine, one of the most respected food publications in the country. It looked perfect from the outside. But inside, she watched four colleagues get promoted while she was denied hers. She was the only one with culinary school training, a master’s degree, and industry experience. She was also the only woman of color.

She left. She took a position as culinary director at the Art Institute of New York City, supervising 30 chef instructors, most of them older men. She was 29.

Through all of this, one thing kept pulling at her. She and her husband Chuck wanted to open a restaurant. They spent two and a half years planning: writing a business plan in small pieces, doing informational interviews, saving what they could. They moved home to Hawaiʻi. Then they started asking people for money.

They heard “no” roughly 25 times before their first outside investor said yes.

“My husband kept saying, the harder I work, the luckier I get. It’s an Arnold Palmer quote my dad shared with me. And I just love that.”

In 2016, Robynne and Chuck opened Fête in Chinatown, Honolulu. Six years later, she became the first woman of Hawaiian ancestry to win a James Beard Award.

The path from ʻAina Haina to that podium in Chicago was not a straight line. It was a long series of searching, stumbling, pivoting, and refusing to stop. And that winding journey is exactly what the research says works.

The insight

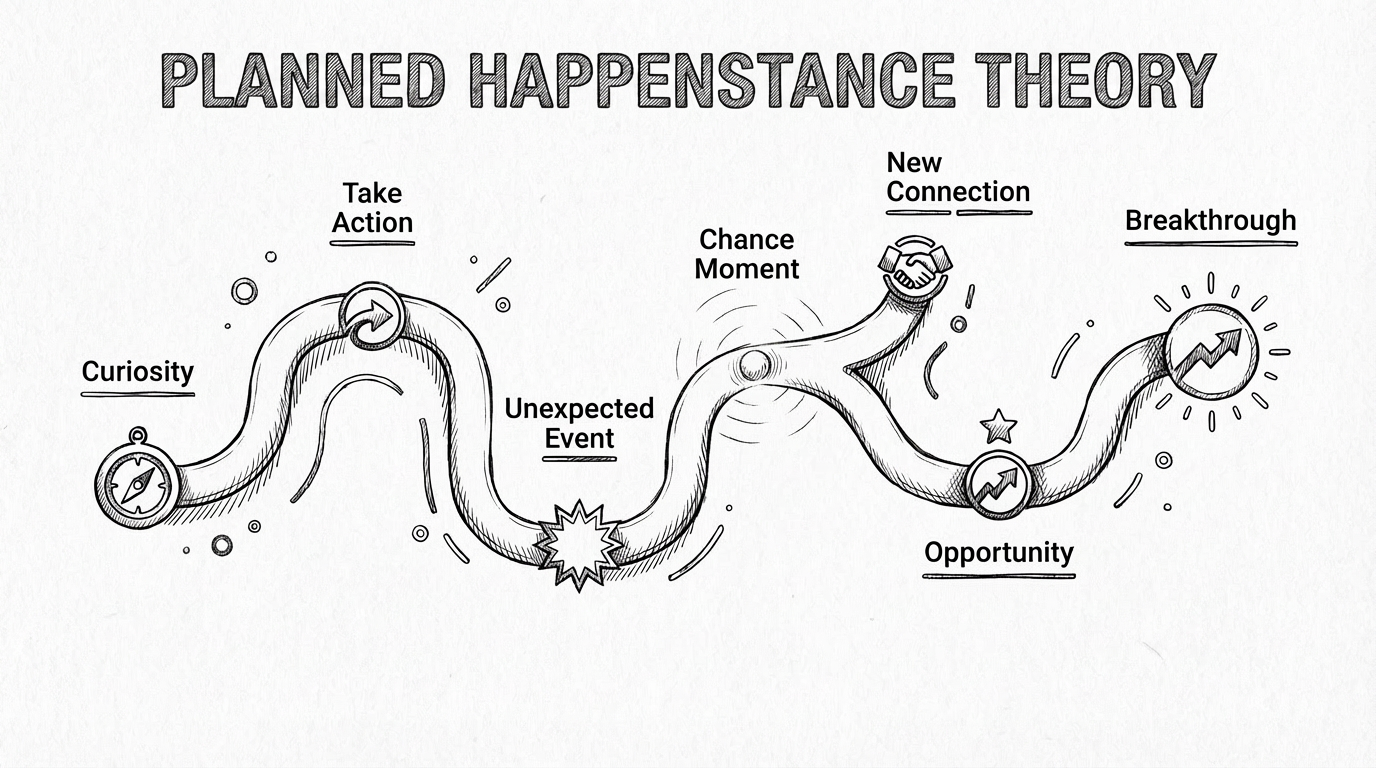

Stanford psychologist John Krumboltz spent decades studying how people actually find fulfilling careers. His conclusion challenged nearly everything traditional career counseling taught. He called it Planned Happenstance Theory.

The core idea: most people do not discover their calling through careful planning.

They discover it through action, curiosity, and a willingness to follow what interests them, even when the destination isn’t clear. The “plan” isn’t a fixed route. It’s a set of behaviors that make you more likely to stumble into the right thing.

Krumboltz identified five skills that separate people who find their way from people who stay stuck:

curiosity (exploring new interests)

persistence (pushing through setbacks)

flexibility (adapting when circumstances change)

optimism (treating obstacles as temporary), and

risk-taking (acting before certainty arrives).

Robynne practiced all five without knowing the theory behind them. She explored law, psychology, dance, food writing, education, and restaurant management before she found the thing that fit. Each pivot looked like indecision from the outside. From the inside, each one was a data point. A narrowing. A refining.

Her mother asked, “Why do you have to be so different?” The answer, it turns out, is that being different was the search in action.

Krumboltz’s research reminds us that the people who find deeply fulfilling work rarely do it by following a clear plan from the start.

They do it by staying in motion long enough for the right thing to find them.

the application

We live in a culture that rewards people who “knew early.”

The kid who wanted to be a doctor at age eight and became one. The athlete who committed to a sport before middle school. The entrepreneur who had a business plan before graduation. These stories get celebrated because they’re clean. They make sense in a linear way.

But most people’s lives don’t work like that.

Most of us try something, feel the friction, adjust, try again. We change majors. We leave jobs. We circle back to old interests with new understanding. And along the way, we carry a quiet fear that all the pivoting means something is wrong with us.

Robynne’s story says the opposite.

Every “wrong turn” taught her something she needed.

Dance gave her discipline.

Food writing gave her craft.

Education gave her management skills.

Therapy gave her self-awareness.

New York gave her resilience.

And all of it, every single detour, fed the restaurant she eventually built.

Planned Happenstance doesn’t mean drifting without intention. It means staying curious, saying yes to things that excite you, and trusting that the dots will connect later even if they don’t connect now.

You don’t need to know the destination to take the next step.

You don’t need a straight line to arrive somewhere meaningful.

You just need to keep moving and pay attention to what lights up.

The clarity you’re waiting for often lives on the other side of action, not before it.

What We Can Steal

Stop waiting for certainty before you move.

Clarity comes from doing, not from thinking. Every experience narrows the search, even the ones that don’t work out.Treat every pivot as a data point.

A winding path isn’t a sign of failure. It’s a sign you’re gathering the information you need to make a better choice next time.Ask for help early, not when it’s dire.

Robynne and Chuck built their restaurant by doing dozens of informational interviews. People are generous when you approach them with genuine curiosity.Let go of the timeline others expect.

Your parents’ vision for your life, society’s benchmarks, your own earlier plans. None of them are obligated to match who you’re becoming.

Mahalo for reading this week’s Mana‘o Bomb.

Next week, we’ll drop another idea from Hawai‘i. A story that sparks growth, resilience, and purpose.

Keep rising. Keep learning.